Why has Pakistan struggled to grow its exports?

Devaluing the currency is not enough. Pakistan must make a concerted effort to improve economic competitiveness to grow its export base.

Students sitting in Econ 101 classes are taught about the J-Curve theory, which in basic terms argues the following:

When a country depreciates its currency, it will at first see a sharp deterioration in its trade balance.

Over time, the balance will improve, as imports become expensive and exports cheaper.

This doesn’t work in the Pakistani context.

Before we get to why, here is some data to set the stage:

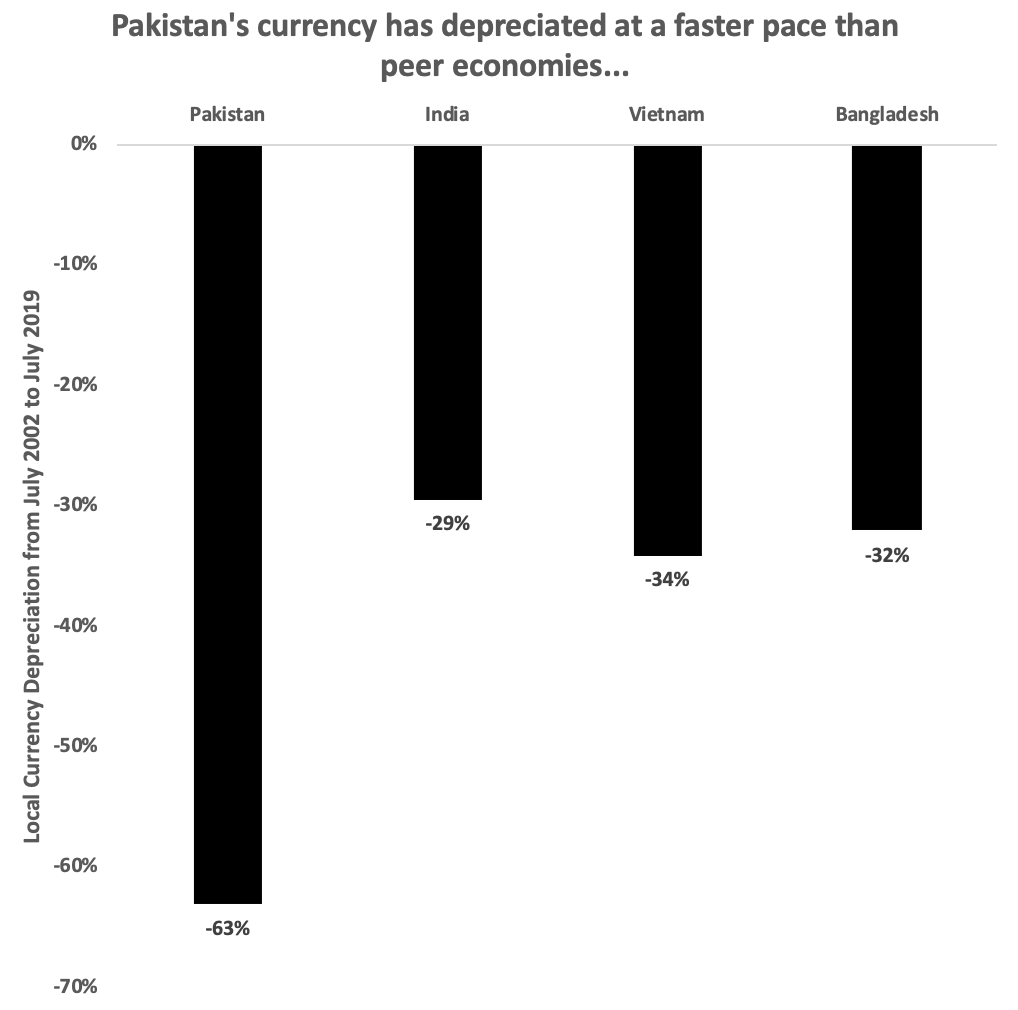

Between 2002 to 2019, the Pakistani rupee has depreciated 63 percent against the US dollar. It used to fetch $0.0166 in July 2002 and by July 2019, it was fetching $0.00616.

This gives us a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of -5.7%, which means that the rupee fell by 5.7% in its value versus the US dollar every year during this period.

During this same period, the country’s exports saw an increase of 136%, going from $9.9 billion in 2002 to $23.35 billion in 2019.

This gives us a CAGR of +5.2%, meaning that exports grew by 5.2% every year, in dollar-denominated terms, during this period.

This data doesn’t mean much on its own.

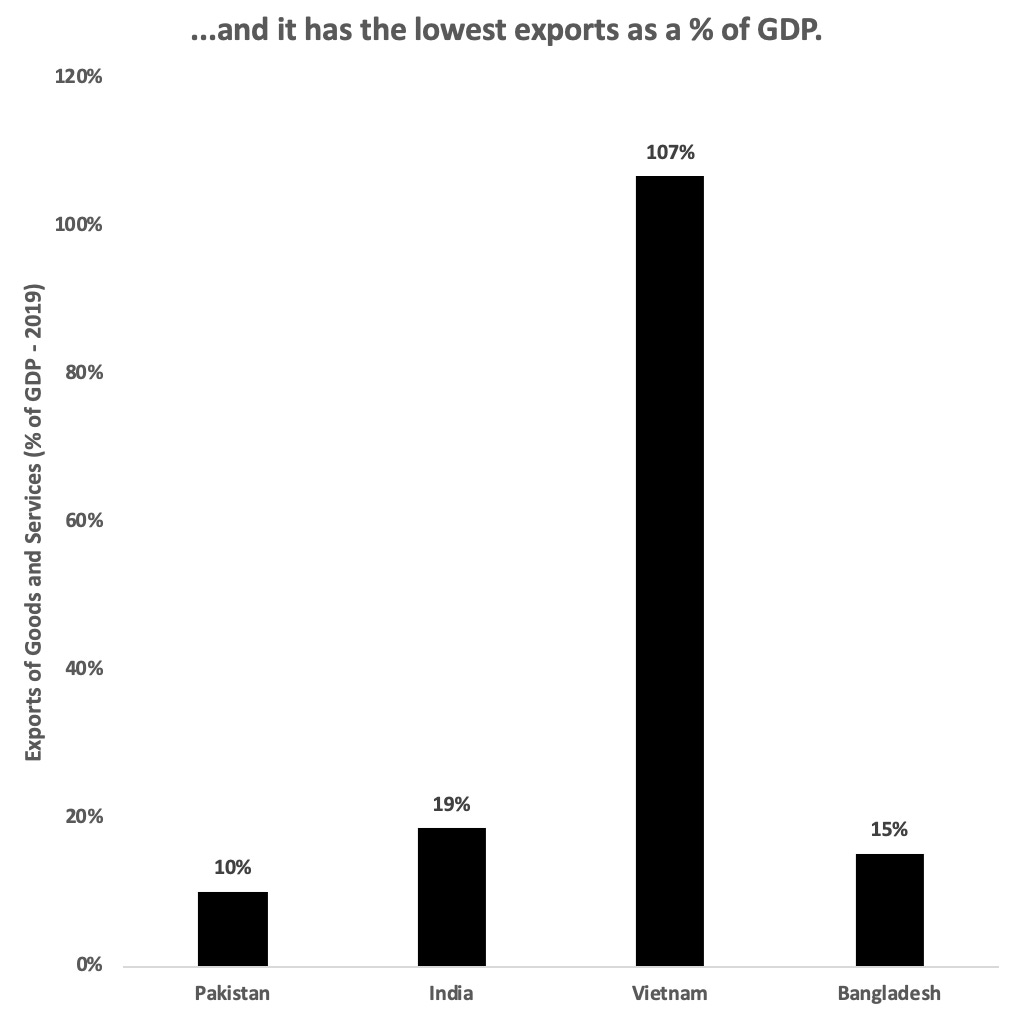

After all, Pakistan is part of a global economy and so its currency’s value and its exports growth must be compared with peer economies, such as India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam.

Among its peers, Pakistan’s performance has been the worst.

Here is what a recent IBA report has to say:

The reduction in imports is due to the massive depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee against US Dollar and other factors like the slowdown in investment in the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project, restrictions on imports such as in the automobile sector, etc. However, the export sector was unable to reap the benefits of this depreciation. This suggests that the country should diversify its exports in terms of commodities as well as destinations.

In 2002, this is what Pakistan was selling to the world:

In 2018, this is what Pakistan is still selling to the world:

As my friend says, there are only so many towels, bed sheets, and t-shirts you can sell all over the world.

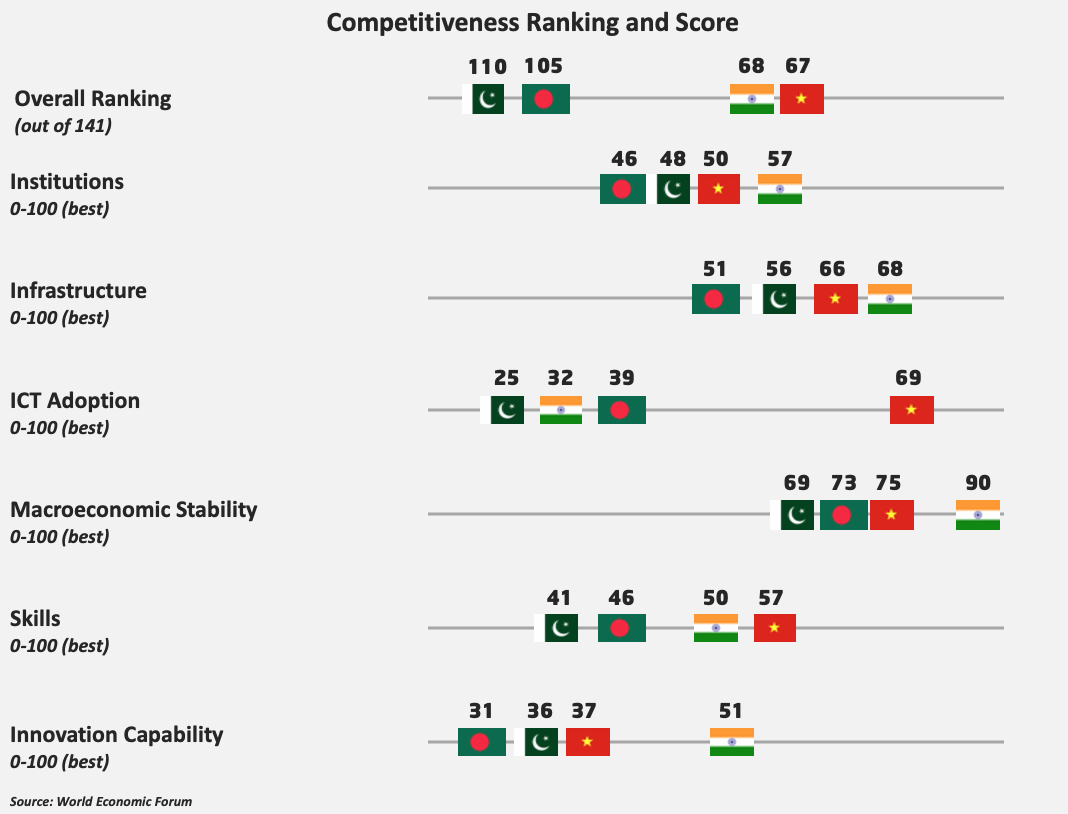

Why is that the case? Because Pakistan is uncompetitive compared to these countries.

It ranks worst or second-worst on all the key pillars of competitiveness measured by the World Economic Forum.

A closer look at the data shows that while the country decent road connectivity, efficient seaports, and competitive productivity & pay, it has a long way to go in terms of educating its workforce and increasing women’s participation in the economy.

So what does Pakistan need to do?

There are a whole host of other issues that have been covered in-depth in many other reports. Some major ones that the government should look at, according to a SDPI-World Bank report, are:

a) regulatory constraints at federal and provincial government levels,

b) high cost of doing business, including energy costs and import tariffs,

c) inadequate trade facilitation and supporting instruments,

d) lack of coordinated support from institutions responsible for export promotion and help towards market and product diversification,

e) weak availability of credit for exports, particularly for potential and new exporters, and

f) an exchange rate regime that is perceived to reinforce the anti-export bias of the de facto trade policy.

Here is another important recommendation from the IBA report:

TDAP and the respective Chambers of Commerce need to work on restructuring their marketing, packaging, pricing, and specialization strategies to increase efficiency and hence overall exports.

Then there is the need to reduce import restrictions, which are actually a barrier to exports. Gonzalo Varela puts it aptly in his blog post:

In this way, import taxes are nothing but export taxes in disguise. Introducing sunset clauses to tariff protection is key to eliminate the anti-export bias.

The government has taken some steps in the right direction when it comes to eliminating this bias, but more needs to be done.

Pakistan needs to stop obsessing over a “strong” currency.

The first thing policy makers must do is maintain market-based exchange rates. Pakistanis are obsessed with a “strong” currency, even though it has proven disastrous for exports and macroeconomic stability.

An overvalued currency prices exporters out of global markets, leading to a loss of market share. It also disincentivizes investments in the export sector, reducing a country’s long-term ability to sell more to the rest of the world.

Imran Khan’s government has so far given the central bank the authority to set market-based exchange rates, and this is a positive development.

But there is still a long, long way to go.

Take a look at any number of export-oriented economies and you will find that they have done so by developing clusters. These clusters exist in or around major urban centers that are efficiently governed and where qualified labor, quality infrastructure, and basic utilities are readily available.

Now look at Karachi, the beating heart of Pakistan’s economy and how it is governed. I have taken a ride from some export-oriented factories to the port, and I can assure you that it is a slow and painful drive.

Cities are where innovation, manufacturing, and trade happens. And for as long as Pakistan cannot figure out an efficient way to govern its cities, it will not be able to grow its exports.

In a world where lead times matter and where a one percent differential in costs can be the difference between winning and losing an export order, Pakistan expects its exporters to remain competitive despite handicapping them every step of the way.

Another area that needs priority focus is the level of skilling and quality of education. Today, even sewing textile products requires workers to have a basic set of skills. A country where the mean years of schooling is 5.1 years (according to the World Economic Forum) will always struggle to diversify its exports base and produce more sophisticated, value-added products.

Then there is the need to increase female labor participation - an economy where the ratio of female to male works is 17% (according to the World Economic Forum) cannot grow sustainably.

South Asia is the least integrated region in the world when it comes to trade. As long as this remains the case, Pakistan cannot grow its export base. Look around the world and you will see that nation-states trade in clusters with their neighbors. Trade flows have historically flown east-west in South Asia, which means that trading with Iran, India, Afghanistan, and beyond is the only way to prosper. Pakistan’s policy makers must seek to utilize the infrastructure developed under CPEC and expand it to integrate with South Asia. This will be difficult, but attempts to normalize relations with Bangladesh, for example, are a positive development.

Most importantly, the country’s policy makers need to focus on the economy, starting from the very top.

While the world is looking to take advantage of supply chains relocating from China for a whole host of reasons, Pakistan’s elite are busy bickering about a whole host of issues that have nothing to do with improving the lives of ordinary Pakistanis. Some of the most recent issues include:

Minus-one formulas.

Threats of bans on social media apps, YouTube, and video games.

NROs, in all their shapes and forms.

The country needs consensus on moving the economy forward and this cannot happen when polarization and political instability is capturing the attention of elected and unelected holders of power.

Today, Pakistan is a problem that must be managed by the rest of the world.

If it can get its act together and grow its exports, the country can quickly become an opportunity that every Pakistani, and the whole world, can benefit from.

Sir, excellent.

Need an article on informal economy of pakistan

The elephant in the room in your army, it decides foreign policy, security policy and increasingly even economic policy .